The Coca-Cola Operating System

How a brown fizzy liquid wrote the original source code for modern capitalism.

I was on a flight back from India last week, watching my youngest daughter inhale red cans of Coca-Cola, when she thought no one was looking. It is a habit she shares with the Oracle of Omaha himself. Warren Buffett, who famously drinks five cans a day to preserve his own morale.

While she was busy fueling a sugar rush at 30,000 feet, I was lost in my thoughts from a crazy month and listening to the second half of the Acquired podcast’s massive deep dive on the very company she was consuming.

As Ben and David broke down the mechanics of the empire in their engaging and enthusiastic way, it hit me. We spend all our time in this newsletter analyzing Fintech and Big Tech. We obsess over “sticky algorithms,” “platform dominance,” and “regulatory pivots.”

But looking at that can in my daughter’s hand, I realized the original Big Tech company isn’t Google, Apple, or Stripe. It’s Coca-Cola.

John Pemberton and Asa Candler didn’t just build a soda company in 1886. They built a $300 billion platform business that dominated usage, scaled at zero marginal cost, and hacked the regulatory environment a century before Silicon Valley existed.

Here is how the “Real Thing” wrote the source code for modern capitalism.

The Algorithm: Pivoting Around Regulation

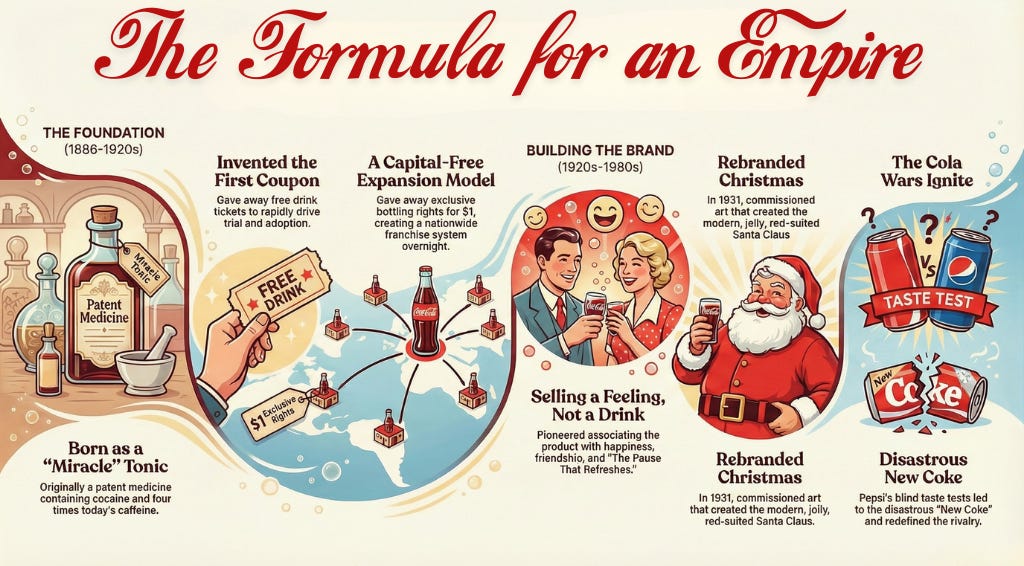

Every great tech stack starts with a killer algorithm. For Coke, the “formula” wasn’t just a recipe. It was a pivot.

The original formula was written by John Pemberton. He was a morphine-addicted Confederate veteran designing a cure for his own pain management. His initial product, “Pemberton’s French Wine Coca,” was a feature-rich mix of alcohol, cocaine, and caffeine. It was the ultimate “sticky” product.

But in 1885, Atlanta passed prohibition laws. This was Coke’s first regulatory headwind. It was the 19th-century equivalent of a crypto crackdown or a GDPR ruling.

Crucially, alcohol was outlawed before cocaine. Pemberton didn’t fold. He refactored the code. He stripped out the alcohol (the wine) and replaced it with sugar, citric acid, and a blend of essential oils known as Merchandise 7X.

He kept the “active users” hooked by retaining the caffeine and, until 1903, the cocaine. This was the Algorithm: a perfectly engineered chemical loop of sugar and stimulation designed to trigger the exact dopamine hits that social media apps optimize for today.

They built a product that wasn’t just consumed. It was programmed into the user’s daily routine.

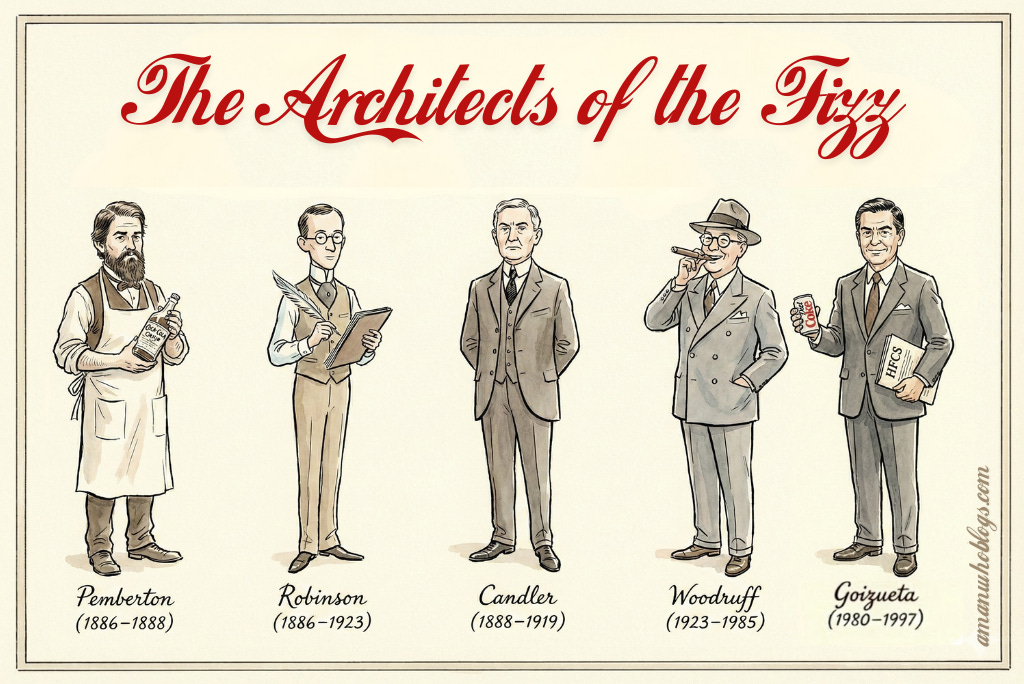

John Pemberton (The Inventor): The pharmacist who created the formula but lacked the vision to scale it.

Frank Robinson (The Namer): The bookkeeper who penned the script logo and invented the first coupon.

Asa Candler (The Scaler): The businessman who bought the rights and built the empire.

Robert Woodruff (The Boss): The CEO who took Coke to war and ruled for 60 years.

Roberto Goizueta (The Alchemist): The chemical engineer who formulated the massive success of Diet Coke and the infamous New Coke.

The Platform: Scaling on Other People’s Hardware

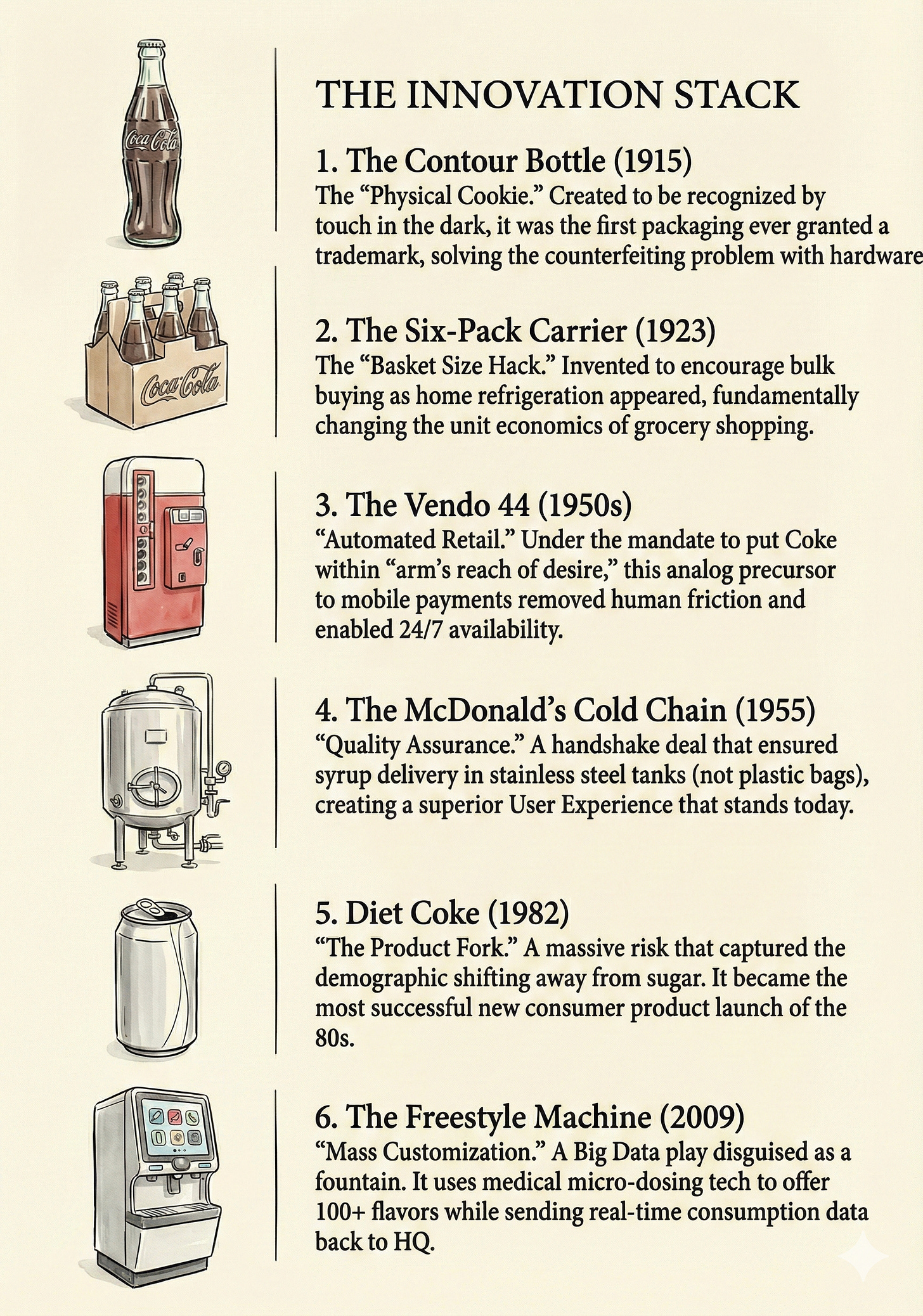

In the tech world, the holy grail is the “platform model” where you own the IP while others build the infrastructure. Think Visa or Uber. Coke invented this in 1899.

When Asa Candler sold the bottling rights for one dollar, he accidentally created the “Coca-Cola System.”

The OS (Coke HQ): Controlled the high-margin concentrate (the IP) and the brand (the User Interface).

The Hardware (The Bottlers): Independent partners who paid for the factories, trucks, and glass.

This was the original “Serverless” architecture. It allowed Coke to scale globally with infinite leverage and almost zero capital investment. While competitors were bogged down buying trucks, Coke was simply shipping syrup. They built the rails and let the rest of the world pay to run the trains.

Growth Hacking: The WWII User Acquisition Strategy

If the bottling system was the platform, World War II was the ultimate “growth hack.”

When the war started, CEO Robert Woodruff issued a decree that would make a modern growth marketer blush: “Every man in uniform gets a bottle of Coca-Cola for 5 cents, wherever he is, and whatever it costs the company.”

This wasn’t charity. It was User Acquisition (CAC) at a global scale.

The US government effectively subsidized Coke’s expansion by treating bottling plants as essential military infrastructure. Coke “Technical Observers” built 64 plants across Europe and Asia on the taxpayer’s dime.

They embedded their product into the most significant geopolitical event of the century. When the war ended, the troops came home, but the infrastructure and the addiction stayed. They had compressed 25 years of global expansion into four years.

The famous 1971 “I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke” campaign. Capturing the moment Coke transitioned from a drink to a symbol of global harmony.

The Glitch: When Data Fails

Even the best algorithms have bugs. For Coke, that bug was New Coke.

In 1985, facing pressure from Pepsi, Coke’s executives trusted the data. Blind taste tests proved users wanted a sweeter product. So they pushed an update called New Coke.

It was a catastrophe.

They had made the classic engineer’s mistake of confusing Utility (taste) with UX (emotion). Users didn’t drink Coke for the flavor profile. They drank it for the memory. The backlash was visceral. It was a real-world version of a user revolt against a bad app interface update.

79 days later, they rolled back the update and returned to “Coca-Cola Classic.” The pivot saved the company. It proved that in consumer tech, brand loyalty is the ultimate moat.

The Lesson

Today, Coke is navigating a new regulatory environment in the war on sugar. They are diversifying into a “Total Beverage” ecosystem with Fairlife, Costa, and Monster, much like Google moving beyond Search or Amazon beyond Books.

But make no mistake. The red can my daughter was crushing on that flight is the result of the same aggressive, scale-at-all-costs, regulation-challenging playbook that defines Silicon Valley today.

They just did it with sugar water instead of software.